At FeedbackNow, we are always looking for data-backed ways to improve operational excellence and the customer experience. We are excited to feature a blog post from Dr. Susan Weinschenk, CEO and Chief Behavioral Scientist, and Guthrie Weinschenk, COO at The Team W, Inc. Dr. Weinschenk is renowned for her work in behavioral science, with decades of experience studying human behavior and its application in business and design. Guthrie is a behavioral economist. Their expertise sheds light on why timing, emotional states, and user interaction are critical to collecting effective, real-time feedback.

Let’s dive into the insights!

The Forgetting Curve: Why Timing Matters

How accurate are memories? We tend to think that memories are stored like video clips in our brains. We find the clip and play it back, right? This seems intuitively right. You think back to when you were last at a family gathering or an annual work celebration. You run the event back in your mind, and it almost seems like you’re watching a movie. We think that memories are like digital recordings of specific facts or events. But that’s not how memories are stored or retrieved.

Memories are not stored intact in a particular part of the brain, ready for you to hit “play”. The latest research on memory shows that memories are a series of triggers. One small thought or smell or something you see triggers a neuron in your brain to fire, which then triggers another neuron and another. Memories are strings of neuron firings. The more you remember something the stronger the connection between neurons becomes, which makes it more likely that a particular chain of neurons fire together. Bits and moments are strung together to form a memory.

You re-create the memory every time you retrieve it. This means that it is possible for the memory to change a little bit every time you remember it. New information or more recent memories can cause you to make changes in existing memories. Every time you remember something it can change a little more.

As consultants, we observe these memory effects during customer and user interviews and testing.

Example 1: During a user test of a clothing website, one person commented that he didn’t like the purple colors on the website. Half an hour later, when we were discussing his experience, he commented on how much he liked the purple color on the website.

Example 2: Another person was using online banking software to send a wire transfer. The user experience of the product was poor. The person was so frustrated that she alternated between using bad language and almost being in tears. Half an hour later she said she thought the site was really easy to use. We told her she didn’t have to say that, that she could be honest about her experience. She looked confused and said, “I am being honest.” It had only been less than an hour, but even after that short amount of time the memories of the experience are often different than the experience itself. Interviews are one of the main ways to get customer and user feedback, but because they rely on memory, they are flawed methods.

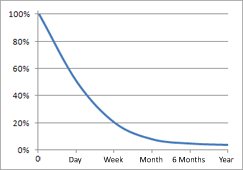

People forget how they feel and what happened. Within one day they have forgotten 60%.

This research goes back to 1885, when Hermann Ebbinghaus created a formula showing the degradation of memories:

R = e(−t/S)

where R is memory retention, S is the relative strength of memory, and t is time. The resulting graph is called Ebbinghaus curve.

Because people forget and because they can recreate memories inaccurately, getting immediate feedback is more accurate than having people fill out a survey later.

Hot and Cold States: Capturing Authentic Experiences

People are strongly influenced by the emotional state they are in. Later, when thinking back on an event, they may not remember how emotionally charged they were in the moment. This may lead to inconsistent predictions about future behavior.

Not only is the memory of emotions often inaccurate, so is the prediction of future emotions. Emotional memory and predictions can be easily influenced.

When people forecast how they will feel in the future, or how they felt in the past, they often extrapolate based on their current situation: also known as “implicit bias”.

Think of being hangry, or going to a grocery store when hungry. While you are at home, and not hungry, you put together your grocery list. Unconsciously you anticipate calmly walking through the store getting the items on your list. But when you get to the store a few hours later, after having run several different errands, when you are stressed and hungry, you will likely tend to buy more and/or different groceries than you planned because of the immediate situation.

- When people are in a “hot” state (hungry/mad/aroused/stressed), they usually predict their future needs or thoughts only in that “hot” state.

- When people are in a “cold” state (full/relaxed/chill/bored) they usually predict their future needs or thoughts only in that “cold” state.

The theory is that hot states act as an amplifier of sorts. Whatever feelings you have in a cold state are amplified several times over in a hot state. This intensification of feelings can change priorities and create tunnel vision.

If someone is stressed because they are late for a flight, angry that the bathroom isn’t clean, or just plain hungry, in order to capture their needs in that moment, you have to capture the data before their state changes or you will not get an accurate response.

When late for a plane, someone may be furious at a long line at the deli checkout counter. Whereas if they have a long layover, the same person may be very relaxed. And when thinking back on the memory (in a survey), if they caught their plane and everything went smoothly, their memories often place them in the state they currently are in.

If they are relaxed at home, they will (incorrectly) remember themselves being in a relaxed (cold) state at the airport. They may remember the bathroom being messy, but they may not remember how mad it made them feel at that moment when looking back later. People recreate a memory of how strongly they felt in the past when retelling a story.

If you do not get the emotional rating in the moment when someone is having an emotion, then that person’s future memory of the event can be biased by up to 3x.

FeedbackNow will likely get more accurate user data than surveys because people are giving real time feedback in the same emotional state.

Morewedge, C. K., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2005). The Least Likely of Times: How Remembering the Past Biases Forecasts of the Future. Psychological Science, 16(8), 626-630. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01585.x

Ariely, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2006). The heat of the moment: the effect of sexual arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 87-98. doi:10.1002/bdm.501

Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2003). Affective Forecasting. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 345-411. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(03)01006-2

Loewenstein, G. (2000). Emotions in Economic Theory and Economic Behavior. American Economic Review, 90(2), 426-432. doi:10.1257/aer.90.2.426

Visual Design: Leveraging Pre-Attentive Processing for Higher Engagement

Visual information comes in through our eyes, but it is our brains that actually determine what we pay attention to and what we ultimately “see”. There are several areas of the brain that process visual information. Some of these areas of the brain process visual information pre-consciously – our brain is interpreting what it is seeing and what we should pay attention to before we even realize what we have seen. Two of these pre-conscious areas are the Pre-attention Visual area and the Fusiform Facial Area (FFA). If you want to grab attention, use should use visual stimuli that these areas are sensitive to. So what are these areas sensitive to?

There are five pre-attention visual areas: V1, V2, V3, V4 and V5. Each visual area has a slightly different role, for example V4 processes color, and V5 processes motion. The pre-attention visual areas are particularly sensitive to the following:

- Diagonal Lines, for example, compared to vertical or horizontal lines

- Size, for example one thing being much smaller or larger than the things around it

- Shape, for example, one thing being a circle when everything else is a square,

- Color, for example, one thing being a different color from everything around it

When the pre-attention visual areas see one of these visual elements it causes neurons to fire in that region of the brain. Let’s say you see a picture that contains circles, but one thing in the picture is a square. The pre-attention visual area that is programmed to notice changes in shape will be stimulated and you will notice that square faster than the circles in the picture. These pre-attention visual areas are especially sensitive to one thing at a time. If you want to grab attention, use only one of these at a time. Using one of these at a time can result in grabbing attention in less than ½ of a second.

In addition to the pre-attention visual areas, the Fusiform Facial Area (FFA) grabs attention when something looks like a face. The FFA is deep in the brain and is sensitive to anything that looks like a face, i.e., two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. People can recognize a face in under 390 ms (less than ½ of a second).

Van Essen, D. C., & Gallant, J. L. (1994). Neural mechanisms of form and motion processing in the primate visual system. Neuron, 13(1), 1-10.

Van Essen, D. C., & Gallant, J. L. (1994). Neural mechanisms of form and motion processing in the primate visual system. Neuron, 13(1), 1-10.

Gladys Barragan-Jason, Gabriel Besson, Mathieu Ceccaldi and Emmanuel J. Barbeau Fast and famous: looking for the fastest speed at which a face can be recognized. Front. Psychol., 04 March 2013 Sec. Cognitive Science Volume 4 – 2013.

Kanwisher, N., McDermott, J., & Chun, M. M. (1997). The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. Journal of Neuroscience, 17(11), 4302-4311.

Tactile Elements: Enhancing the User Experience

People enjoy pressing buttons. Research shows that button pressing can provide a satisfying and enjoyable experience due to the tactile and interactive nature of button pressing, as well as the sense of control and agency that it provides.

Actual buttons, or digital buttons designed to mimic actual buttons, will have increased engagement compared with “flat” digital buttons.

Pressing buttons is a conditioned automatic response. People will reach out to push a button before they realize they are doing so. FeedbackNow sensors that use actual buttons will be more likely to be used than an online survey.

MacLean, K. E. (2008). Tactile feedback and user experience in touch interfaces. CHI’08 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3853-3856.

Plotnick, R. (2018). Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing. MIT Press.

These insights from the Team W highlight the intricate relationship between behavioral science and feedback mechanisms. Effective feedback is the foundation of operational excellence, but it’s only as good as its timing, authenticity, and engagement. By integrating principles of behavioral science, FeedbackNow enables organizations to gather real-time insights that truly reflect the user experience. From addressing the Forgetting Curve to leveraging visual and tactile elements, these approaches enhance the accuracy and impact of feedback.

As organizations continue to prioritize customer-centric strategies, tools like FeedbackNow stand at the forefront, empowering teams to make informed decisions and deliver experiences that resonate.